Boston Region Metropolitan Planning Organization 2023 Language Assistance Plan

Project Manager

Betsy Harvey

Project Principal

Sarah Philbrick

Data Analysts

Erin Maguire

Graphics

Adriana Fratini

Cover Design

Adriana Fratini

Editor

David Davenport

The preparation of this document was supported

by MPO Combined PL and 5303 #118967.

Central Transportation Planning Staff is

directed by the Boston Region Metropolitan

Planning Organization (MPO). The MPO is composed of

state and regional agencies and authorities, and

local governments.

For general inquiries, contact

Central Transportation Planning Staff 857.702.3700

State Transportation Building ctps@ctps.org

Ten Park Plaza, Suite 2150 ctps.org

Boston, Massachusetts 02116

The Boston Region Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) operates its programs, services, and activities in compliance with federal nondiscrimination laws including Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Title VI), the Civil Rights Restoration Act of 1987, and related statutes and regulations. Title VI prohibits discrimination in federally assisted programs and requires that no person in the United States of America shall, on the grounds of race, color, or national origin (including limited English proficiency), be excluded from participation in, denied the benefits of, or be otherwise subjected to discrimination under any program or activity that receives federal assistance. Related federal nondiscrimination laws administered by the Federal Highway Administration, Federal Transit Administration, or both, prohibit discrimination on the basis of age, sex, and disability. The Boston Region MPO considers these protected populations in its Title VI Programs, consistent with federal interpretation and administration. In addition, the Boston Region MPO provides meaningful access to its programs, services, and activities to individuals with limited English proficiency, in compliance with U.S. Department of Transportation policy and guidance on federal Executive Order 13166.

The Boston Region MPO also complies with the Massachusetts Public Accommodation Law, M.G.L. c 272 sections 92a, 98, 98a, which prohibits making any distinction, discrimination, or restriction in admission to, or treatment in a place of public accommodation based on race, color, religious creed, national origin, sex, sexual orientation, disability, or ancestry. Likewise, the Boston Region MPO complies with the Governor's Executive Order 526, section 4, which requires that all programs, activities, and services provided, performed, licensed, chartered, funded, regulated, or contracted for by the state shall be conducted without unlawful discrimination based on race, color, age, gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, religion, creed, ancestry, national origin, disability, veteran's status (including Vietnam-era veterans), or background.

A complaint form and additional information can be obtained by contacting the MPO or at http://www.bostonmpo.org/mpo_non_discrimination.

To request this information in a different language or in an accessible format, please contact

Title VI Specialist Boston Region MPO 10 Park Plaza, Suite 2150 Boston, MA 02116 civilrights@ctps.org

By Telephone: 857.702.3700 (voice)

For people with hearing or speaking difficulties, connect through the state MassRelay service:

Relay Using TTY or Hearing Carry-over: 800.439.2370

Relay Using Voice Carry-over: 866.887.6619

Relay Using Text to Speech: 866.645.9870

For more information, including numbers for Spanish speakers, visit https://www.mass.gov/massrelay.

Abstract

Executive Order 13166—Improving Access to Services for Persons with Limited English Proficiency—directs recipients of federal funding to “ensure that the programs and activities they normally provide in English are accessible to LEP persons and thus do not discriminate on the basis of national origin in violation of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.” In response to subsequent regulations developed by the United States Department of Transportation, this Language Assistance Plan (LAP) describes the language needs of residents within the 97 municipalities served by the Boston Region Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) and the oral and written language assistance that the MPO provides to meet those needs. As the MPO is a recipient of federal funding from the Federal Transit Administration and the Federal Highway Administration, this LAP meets the requirements set forth by these agencies regarding the provision of language assistance in the MPO’s activities and programs.

As a recipient of federal funding from the Federal Transit Administration and the Federal Highway Administration, the Boston Region Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) is required to develop this Language Assistance Plan (LAP) that describes the population with limited English proficiency (LEP) in the Boston region and the MPO approach to providing language assistance.

To determine language needs, MPO staff conducted a four-factor analysis as required by recipients of federal funding:

The following sections summarize the results of the four-factor analysis.

MPO staff used the US Census Bureau’s American Community Survey Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS) data to identify the percentage and number of people in the MPO region who have LEP and the languages they speak at home. According to the most recent 2017–21 PUMS, there are approximately 372,079 people with LEP in the Boston Region, approximately 11.1 percent of the population. Of those, approximately 354,449 speak Safe Harbor languages, or 95.3 percent of people with LEP. Safe Harbor languages are those that are spoken by at least 1,000 people or five percent of the population, whichever is less. There are 26 Safe Harbor languages in the Boston region, the top five being Spanish, Chinese languages, Portuguese (including Cape Verdean Creole), Haitian, and Vietnamese. Since the 2012–16 PUMS, the estimated percentage of residents with LEP in the region increased from 10.5 percent to 11.1 percent.

Staff sought additional sources of data on non-English languages spoken in the region that are available at a smaller geography than PUMS data. Staff used Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (DESE) data to identify the languages spoken by English language learners (ELL) in public school districts within the Boston region.1 According to 2022–23 academic year data, 16.8 percent of primary and secondary school students are ELLs, out of 412,982 students. The five most commonly spoken languages are Spanish, Portuguese (including Cape Verdean Creole), Haitian Creole, Chinese languages, and Arabic. Comparing ELL to PUMS data suggest that people with LEP are more likely to be families with children in school, particularly speakers of Portuguese and Spanish, which have higher percentages of ELL speakers than the overall LEP population.

Because of the nature of its activities, the MPO has variable and unpredictable contact with people with LEP. MPO staff conduct engagement activities on a regular basis, such as biweekly MPO board meetings, monthly meetings of the MPO’s Advisory Council, the development of the annual Transportation Improvement Program (TIP) and the Unified Planning Work Program (UPWP), and the development of the Long-Range Transportation Plan (LRTP), which is done every four years. Targeted engagement with LEP populations is part of these activities, but the frequency varies year to year. In addition, each year the MPO funds several studies, most of which contain a significant engagement element. The level of LEP engagement varies, depending on the study topic, study area, and resources available. In addition, the website is widely used by all members of the public as a contact point with the MPO; the MPO uses the translator service Localize to translate content on its website.

The MPO plans and funds transportation projects and carries out studies within the Boston region. Although it is not an implementing agency, MPO-funded transportation projects can have a significant effect on residents’ mobility and quality of life. Therefore, the MPO invests considerable effort to conduct inclusive public engagement to ensure all people have meaningful opportunities to influence MPO decisions and that projects the MPO funds reflect their needs. Engagement is conducted largely through the MPO’s programs, which help guide and inform investment decisions. Programs fall into several categories:

The precise nature and extent of the public engagement varies year to year but includes in-person and online meetings organized by MPO staff, as well as MPO staff attendance at existing public events and at partner organizations’ events. MPO staff view relationship building with LEP communities and organizations that serve them as an ongoing activity, whether or not it is for a specific program or activity. This allows staff to build trust over time, understand community needs, increase transparency, and ensure that people with LEP have opportunities to be involved early and often.

Because of the large number of Safe Harbor languages spoken in the Boston region, and the undue cost of providing this number of translations coupled with the limited demand, the MPO does not translate all vital documents into each language. Instead, the MPO budgets sufficient funds to translate vital documents into the five languages most widely spoken by people with LEP, which comprises more than 80 percent of people with LEP:

To reduce the cost burden on the MPO and to tailor translations to community needs, engagement materials are translated only into the languages most commonly spoken in that community, which may or may not be among the top five listed above, depending on the needs of the community. In addition, only executive summaries are translated for the longer vital documents due to their length. All of these documents are also made available in HTML on the MPO website, which can be translated using the MPO’s web translator, Localize. If a person requests a translation for a language other than these five, staff make every effort to accommodate it based on the resources available. If resources are limited, staff work with the requester to offer alternatives that meet their needs. Strategies for doing so depend on the size of the document being translated. Many smaller documents can be translated by professional translators. If resources do not allow this, staff will use machine translator services, such as Localize and Google Translate, to provide the translation.

Resources are also allotted to provide interpreter services upon request at MPO-hosted meetings (such as board meetings). As with translations, staff bring interpreters to engagement meetings and events where it is expected people with LEP will be in attendance. Each year, staff budget for an estimated number of events where interpreters will be needed. Events are based on upcoming MPO studies and the expected public engagement that will be needed; meetings with community groups that serve people with LEP that staff are seeking to build relationships with; and attendance at events where people with LEP are likely to attend (such as farmers markets).

For all MPO-hosted events and meetings, the MPO provides interpreter services upon request, including virtual meetings. Staff also schedule interpreters at external events where it is expected that there will be people with LEP, using information from community partners, Census data, and DESE data. The MPO asks people to request interpreter services at least five calendar days in advance of an event, but staff make every effort to accommodate requests made with less notice.

The MPO prioritizes providing written translations of vital documents, as required by federal regulations. Vital documents are those that contain information that is critical for obtaining MPO services or those required by law. They include

The MPO may only provide executive summary translation of certain vital documents because of their length:

Most vital documents are translated into the top five most commonly spoken languages: Spanish, Chinese (both Simplified and Traditional translations are made available), Portuguese, Haitian Creole, and Vietnamese. Members of the public may request translations in additional languages, which the MPO will make every effort to fulfill. For translations needed for a scheduled MPO meeting or event, MPO staff asks that requests are made at least five days in advance, although requests made with less time will be fulfilled if possible.

At engagement events, document translations are provided in languages that are most relevant to the communities in which they are being conducted, regardless of whether it is one of the five languages listed above. Staff consult trusted partner community groups and use US Census and DESE data to identify languages and if a particular dialect is likely to be spoken (such as Brazilian Portuguese). Translated materials are provided at events to allow non-English speakers to obtain the same information available to English speakers.

Strategies to increase engagement with people with LEP are focused on more effectively targeting the MPO’s engagement to communities with higher rates of people with LEP to better understand and address language needs throughout the region. Methods include direct in-person engagement by attending meetings held by organizations that include or serve people with LEP and tabling at community events, developing materials tailored to attendees, and provision of interpretation services, informed by staff’s analysis of where particular languages are spoken. Staff are also developing long-term, non-project-based relationships with community-based organizations that include and/or serve people with LEP, and exploring partnerships with these organizations that include providing compensation or incentives to encourage their engagement. This helps build trust between the MPO and the communities it serves and allows staff to solicit input more effectively from people with LEP at important points during project and planning work.

While the MPO has been able to provide language translation services with existing resources thus far, the region continues to attract diverse populations. Therefore, the MPO will continue to monitor the need for translation and interpretation services based on the Four-Factor Analysis, the number of requests received, and changing demographics of the region. Updates to our language assistance services are made as needed, at least every three years. In the interim, staff will explore new sources of data that provide more nuanced understanding of the language needs of residents in the region and new technologies that expand the reach of MPO activities to more people. To ensure more people with LEP are aware of the MPO and services and programs it provides, staff will continue to build relationships with community organizations that serve people with LEP.

The Boston Region Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) is committed to ensuring that people with limited English proficiency (LEP) are neither discriminated against nor denied meaningful access to and participation in the programs, activities, and services provided by the MPO. As a recipient of federal funding, the MPO has developed this Language Assistance Plan (LAP) to describe how the MPO provides language assistance to people with LEP to ensure meaningful access to the MPO’s transportation planning process and decision-making.

Conducting meaningful public engagement is a core function of the MPO, critical to ensuring that regional transportation planning is conducted in a fair and transparent manner, and that its investments meet the needs of the Boston region’s residents. While this LAP is designed to meet federal requirements, it also supports MPO staff in the development and implementation of public engagement activities. These are described in the MPO’s Public Engagement Plan.

In accordance with federal guidance, this LAP is updated at least every three years. As required, the LAP assesses the following four factors when determining language needs of people with LEP served by the MPO:

Chapter 2 describes the results of this Four-Factor Analysis, Chapter 3 describes the MPO’s approach to providing language assistance and strategies for increasing engagement with people with LEP in the Boston region, and Chapter 4 shares how the LEP is monitored and updated.

Chapter 2—Determining Language Needs

This chapter discusses the results of the Four-Factor Analysis that is required to determine the language needs of residents of the Boston region.

The Boston Region Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) uses language data from the American Community Survey (ACS), the main source of English language ability in the United States. These data are reported through the Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS). Because the PUMS data are reported at a large geography, staff also gathered data on English language learners (ELL) at public primary and secondary schools to provide a more detailed picture of language needs in the Boston region.

PUMS reports ACS data in untabulated records of individual people or housing units. Because of the disaggregated nature of the data, they are subject to more stringent privacy controls, resulting in the data being only available at a larger geography—the Public Use Microdata Area (PUMA), which are geographies with populations of at least 100,000. Because PUMAs do not follow MPO boundaries, LEP language data reported here are summed for the PUMAs for which the majority of its geography overlapped with the MPO region. (See Appendix A for a list of PUMAs used in this analysis.)

Table 1 shows the Safe Harbor languages spoken in the Boston region using 2017–21 ACS data. Safe Harbor languages are those that are spoken by at least 1,000 people or five percent of the population, whichever is less. It also shows the percent change from the 2012–16 ACS.2 Twenty-six languages pass the threshold for a Safe Harbor language in the region, the speakers of which make up 95.3 percent of all people with LEP. Since the 2012–16 ACS, the estimated total number of residents in the Boston region with LEP has increased from 10.5 percent to 11.1 percent of the Boston region’s population.

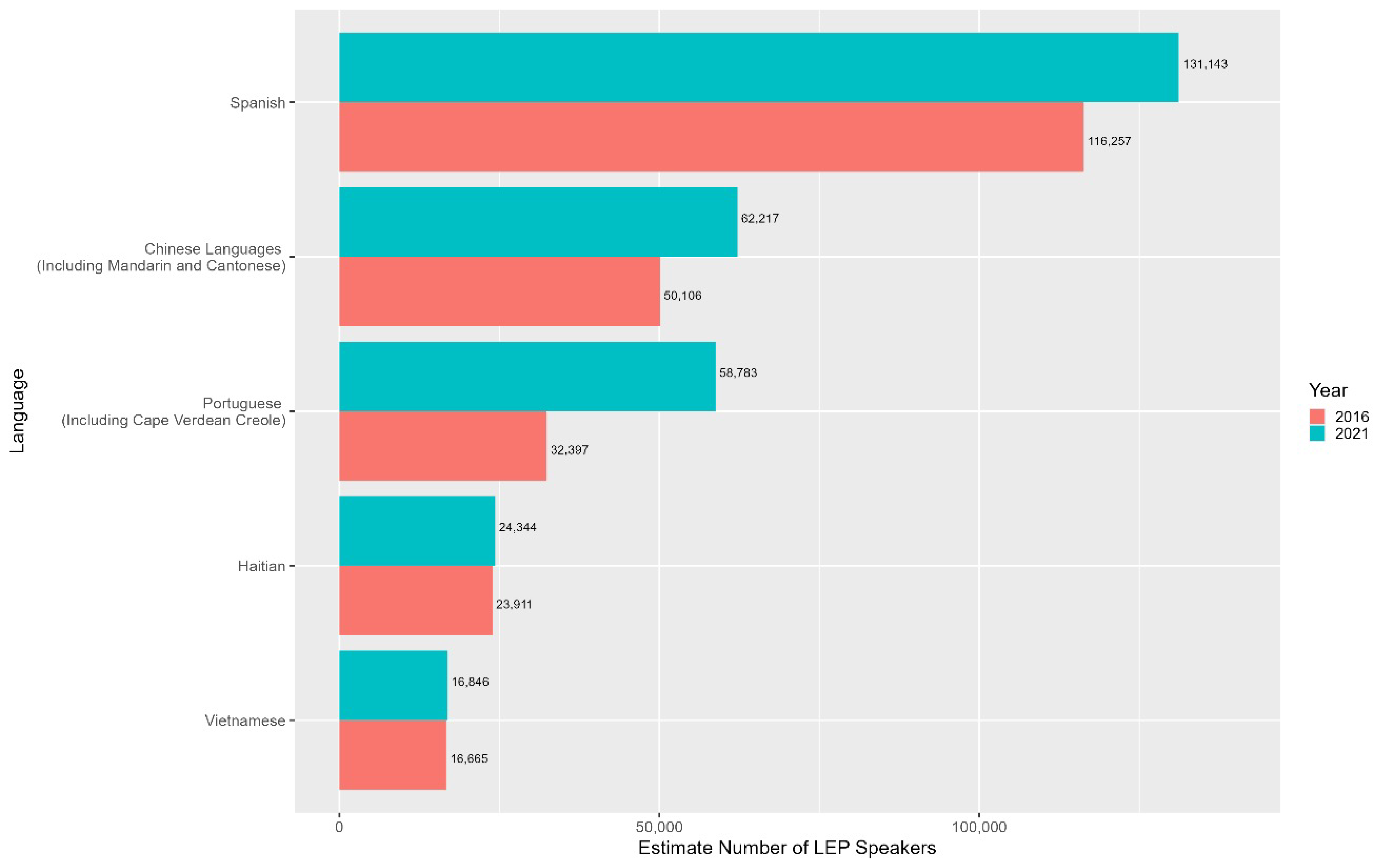

The Portuguese-speaking population saw the greatest increase since the 2012–16 ACS, growing from approximately 32,000 to 58,000 LEP speakers, a growth of 81.4 percent. Other languages with a large increase include Chinese languages, Hindi, Bengali, Telugu, and Farsi. The languages with the greatest decreases include Italian, Arabic, Japanese, Polish, and Russian.

Table 1

Safe Harbor Languages Spoken in the Boston Region

Language |

Estimated Number of People with LEPa |

Percent Change from 2012–16 |

Percent of LEP Speakers |

Percent of Boston Region Population |

Spanish |

131,143 |

12.2% |

35.2% |

3.9% |

Chinese languagesb |

62,217 |

24.2% |

16.7% |

1.9% |

Portuguesec |

58,783 |

81.4% |

15.8% |

1.8% |

Haitian |

24,344 |

1.8% |

6.5% |

0.7% |

Vietnamese |

16,846 |

1.1% |

4.5% |

0.5% |

Russian |

10,737 |

-4.7% |

2.9% |

0.3% |

Arabic |

7,947 |

-25.2% |

2.1% |

0.2% |

Italian |

4,904 |

-26.4% |

1.3% |

0.1% |

Korean |

4,304 |

1.2% |

1.2% |

0.1% |

Greek |

4,040 |

3.4% |

1.1% |

0.1% |

Albanian |

3,629 |

19.9% |

1.0% |

0.1% |

Hindi |

3,510 |

44.7% |

1.0% |

0.1% |

Khmer |

2,493 |

-12.2% |

0.7% |

0.1% |

Japanese |

2,357 |

-26.2% |

0.6% |

0.1% |

Bengali |

2,177 |

81.0% |

0.6% |

0.1% |

Nepali |

2,061 |

9.2% |

0.6% |

0.1% |

Farsi |

1,793 |

49.0% |

0.5% |

0.1% |

Gujarati |

1,708 |

-0.4% |

0.5% |

0.1% |

Amharic |

1,462 |

18.4% |

0.4% |

0.0% |

Armenian |

1,275 |

12.3% |

0.3% |

0.0% |

Punjabi |

1,234 |

-28.0% |

0.3% |

0.0% |

Polish |

1,197 |

-35.1% |

0.3% |

0.0% |

Telugu |

1,112 |

56.4% |

0.3% |

0.0% |

Tamil |

1,086 |

16.9% |

0.3% |

0.0% |

Thai |

1,085 |

-2.6% |

0.3% |

0.0% |

Urdu |

1,005 |

88.6% |

0.3% |

0.0% |

Total Safe Harbor Language Speakers |

354,449 |

14.1% |

95.3% |

10.5% |

Total People with LEP |

372,079 |

13.4% |

100% |

11.1% |

a ACS values are estimates. Because PUMAs do not align with MPO boundaries, PUMAs that are mostly within the MPO region are included in this analysis.

b Chinese languages include Mandarin and Cantonese, among others.

c Includes Cape Verdean Creole.

LEP = Limited English proficiency. MPO = Metropolitan Planning Organization. PUMA = Public Use Microdata Area.

Source: American Community Survey Public Use Microdata Sample, 2012–16 and 2017–21.

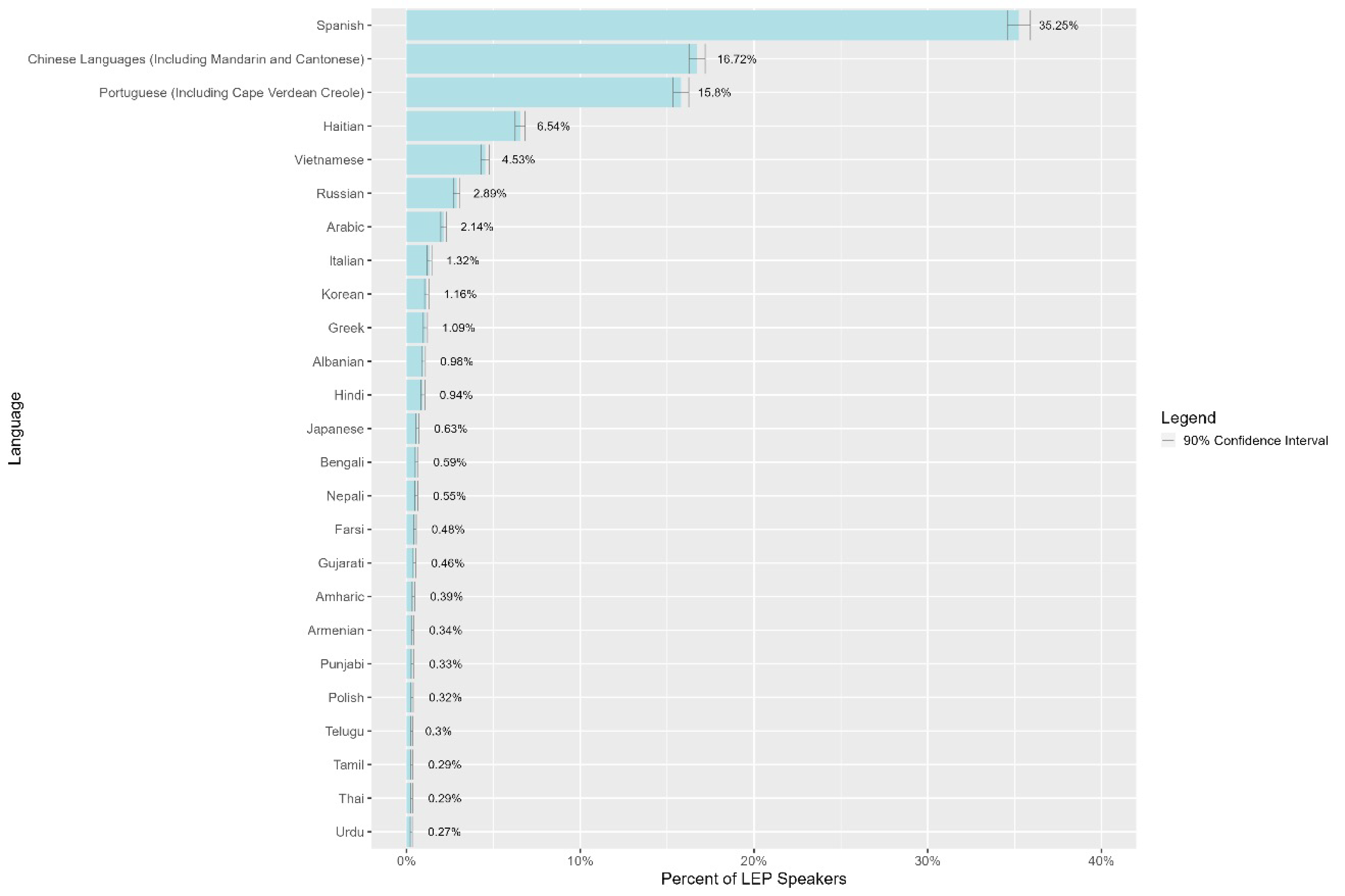

Figure 1 shows the percentage of people with LEP who speak each Safe Harbor language, and the margins of error in the underlying data. Figure 2 shows the estimated growth of the population of each of the top five Safe Harbor languages in the Boston region.

Figure 1

Percent of Safe Harbor Language Speakers

LEP = limited English proficiency.

Figure 2

Change in Number of Top Five Safe Harbor Language Speakers

LEP = limited English proficiency.

To further understand the language needs of people with LEP, staff used 2017–21 ACS data on the place of birth of foreign-born residents to better understand which dialects of the Safe Harbor languages are most widely spoken in the region, and therefore provide appropriate language services. Mainland China and Brazil are the two most common places of birth for the foreign-born population, accounting for 11.5 and 7.3 percent of that population in the Boston region, respectively. This indicates a need to provide translations in Simplified Chinese and Brazilian Portuguese. Approximately 1.8 percent of foreign-born residents are from Hong Kong and Taiwan, where Traditional Chinese is the official written language.

Among likely countries where Spanish is the primary language, in the Boston region El Salvador is the most common country of origin for the foreign-born population (30 percent), followed by Guatemala (17 percent), and Columbia (15 percent). This indicates that Spanish speakers are more likely to speak the Latin American dialect of Spanish. While dialects are generally mutually intelligible, this can inform the MPO’s decisions regarding choosing appropriate dialects for translations, when available, and ensuring interpreters speak the appropriate dialect for the community.

Staff sought additional sources of data on non-English languages spoken in the region that are available at a smaller geography. The Department of Elementary and Secondary Education collects data on the number of students who are English language learners (ELL) in each public school district, as well as the languages they speak.3 It is assumed that if a student is an ELL, their parents have limited English proficiency. While this definition does not correlate perfectly with the United States Department of Transportation’s LEP definition, it does allow staff to identify where language needs are present at smaller geographies, which is helpful for public engagement purposes. According to 2022–23 academic year (AY) data, 16.8 percent of primary and secondary school students in public districts in the Boston region were ELLs, out of 412,982 students. The percentage of ELL students in public schools in the Boston region is greater than the percentage of LEP speakers, which suggests that a significant portion of Massachusetts immigrants are families with school-aged children.

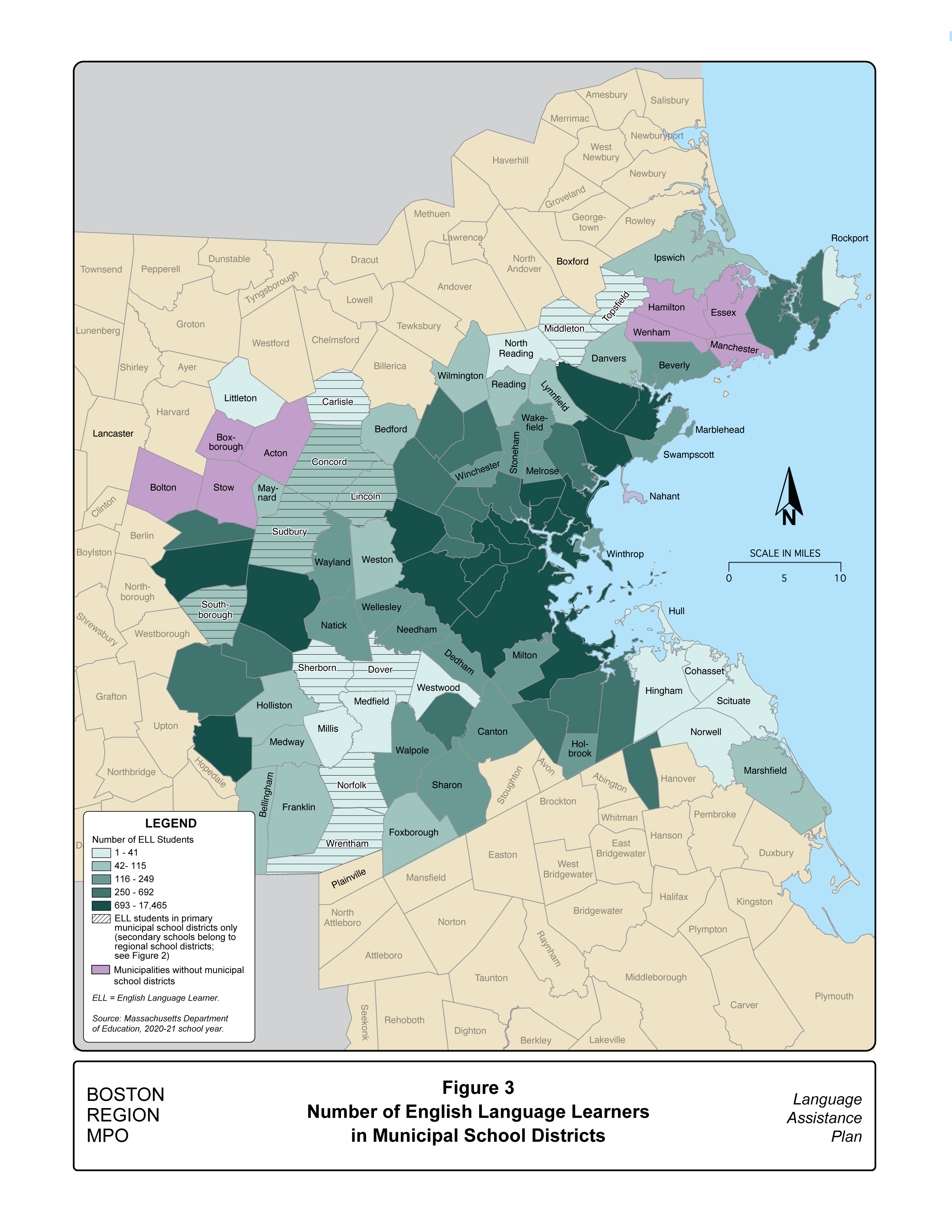

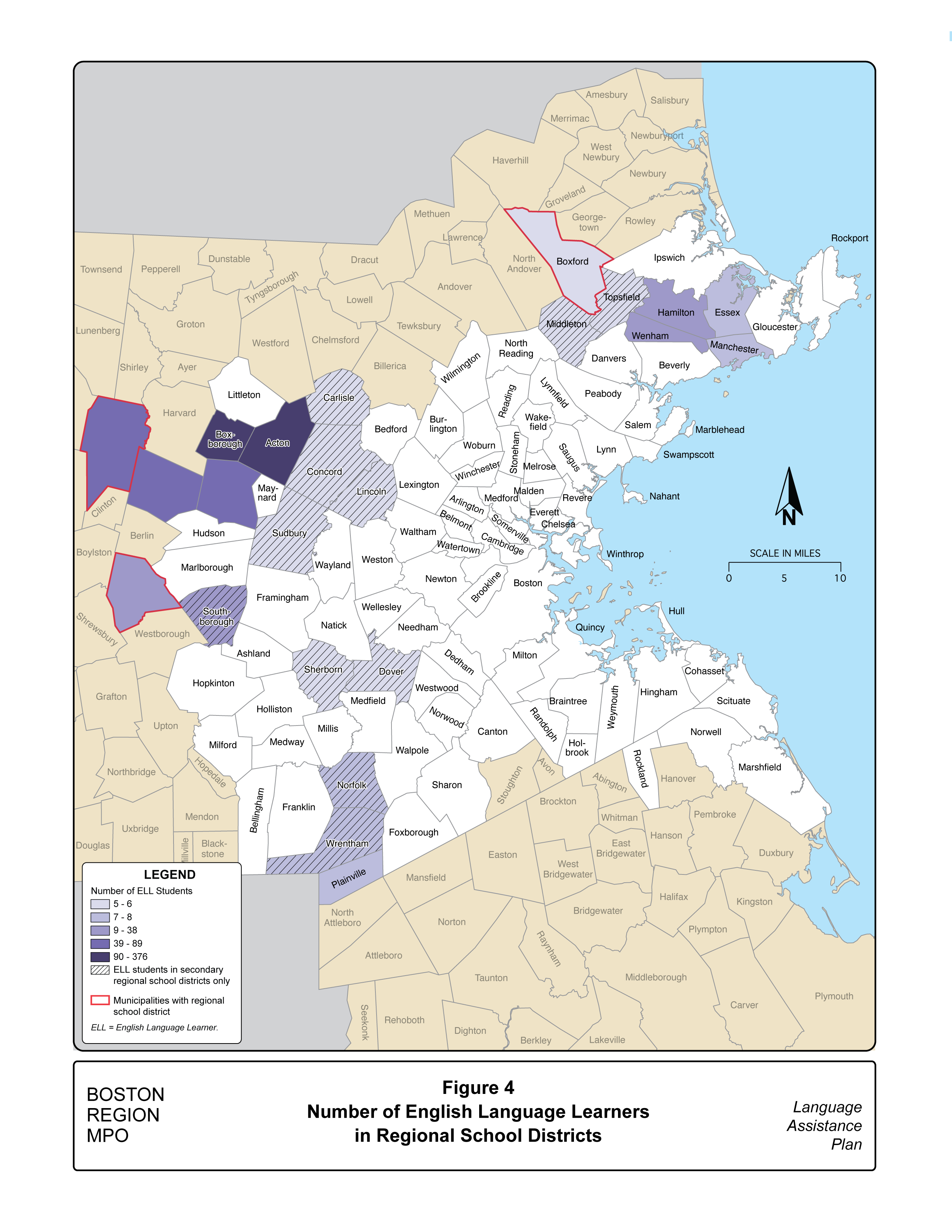

Figure 3 shows the number of ELL students in municipal public school districts, while Figure 4 shows the number of ELL students in regional public school districts.4 The school districts with the most ELL students are those in and around Boston and Framingham, trends consistent with the 2020 LAP, which used 2020–21 AY year data.

Figure 3

Number of English Language Learners in Municipal School Districts

ELL = English language learners.

Figure 4

Number of English Language Learners in Regional School Districts

ELL = English language learners

Table 2 shows the 10 languages spoken most frequently by ELLs. Since the 2020–21 AY, the number of ELL students has increased significantly, with those speaking each of the top 10 ELL languages increasing. The largest increases were in the number of ELL students who speak Portuguese with a 78.3 percent increase and Arabic with an increase of 49.0 percent. Since the 2020–21 AY, Korean has become one of the 10 most commonly spoken languages by ELLs, replacing Somali.

Table 2

Top 10 Non-English Languages Spoken by English Language Learners

Language |

Number of ELL Students |

Percent of ELL Students |

Percent Change from 2020–21 AY |

Spanish |

34,401 |

49.7% |

39.8% |

Portuguesea |

15,296 |

22.1% |

78.3% |

Haitian Creole |

3,098 |

4.5% |

31.8% |

Chinese languages |

3,054 |

4.4% |

10.6% |

Arabic |

2,043 |

3.0% |

48.9% |

Vietnamese |

1,158 |

1.7% |

0.2% |

Russian |

856 |

1.2% |

29.3% |

Japanese |

564 |

0.8% |

40.6% |

French |

502 |

0.7% |

25.8% |

Korean |

443 |

0.6% |

N/A |

a Includes Cape Verdean Creole

AY = academic year. ELL = English language learner.

Source: Massachusetts Department of Education, 2020–21 and 2022–23 academic years.

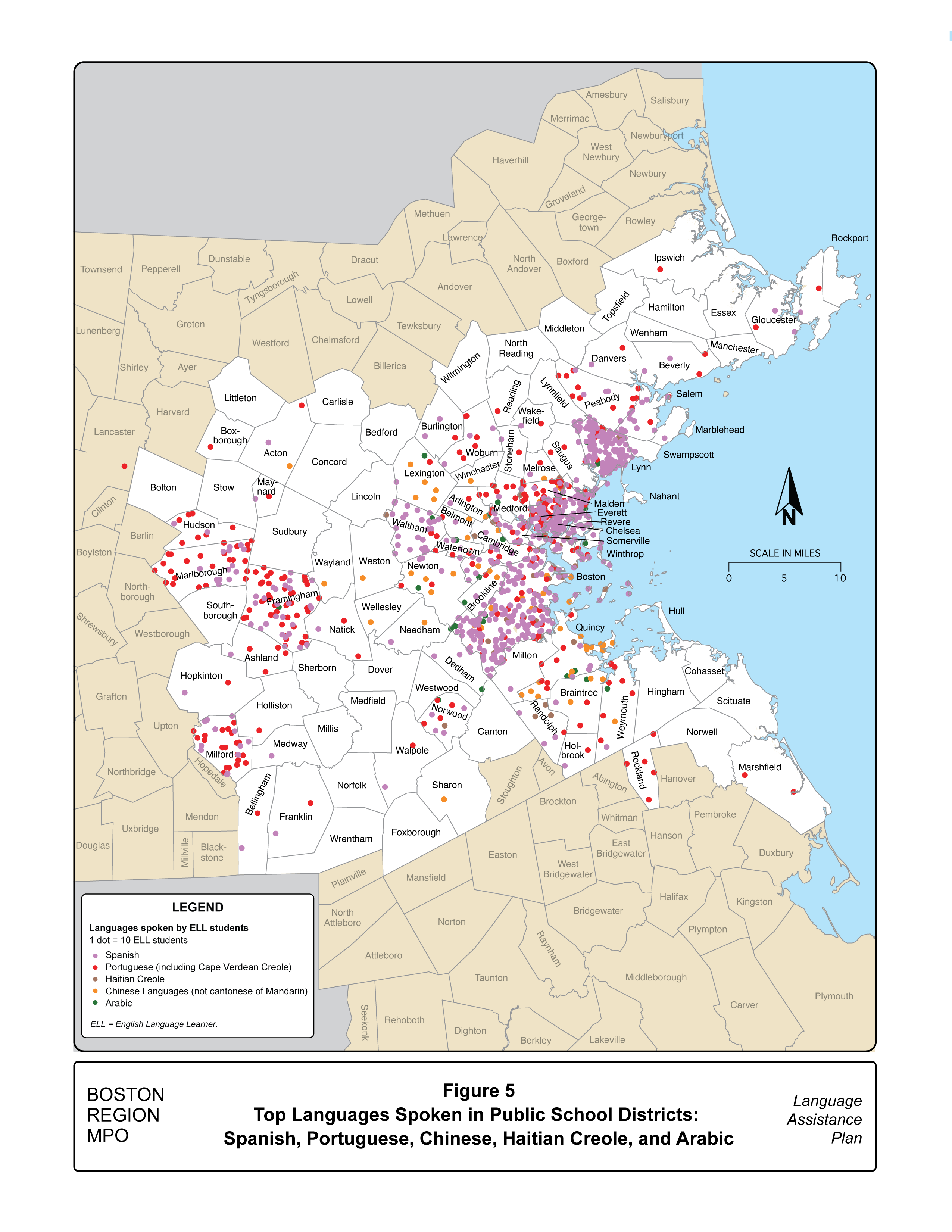

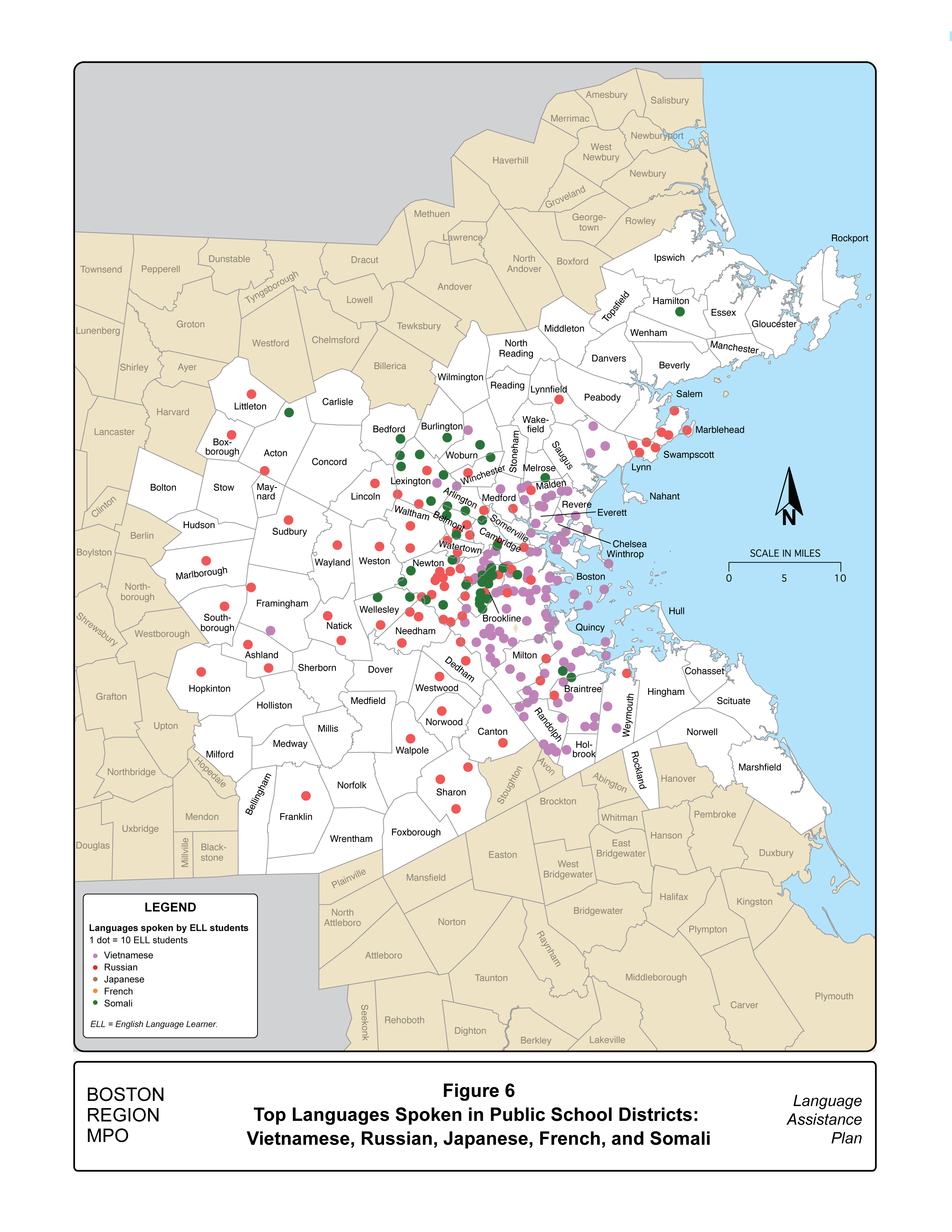

Figures 5 and 6 show the distribution of these top 10 languages spoken by ELLs within the MPO region. Note that the dots are randomly distributed within each school district and do not represent the actual locations of ELL students.

Figure 5

Most Commonly Spoken Languages in Public School Districts: One Through Five

[PLACEHOLDER]

ELL = English language learner.

Figure 6

Most Commonly Spoken Languages in Public School Districts: Six Through 10

[PLACEHOLDER]

ELL = English language learner

Spanish is the most widely spoken language among ELLs, followed by Portuguese, Haitian Creole, Chinese languages, and Arabic. For three languages, there is a higher percentage of ELLs than people with LEP—Spanish (49.7 percent of ELLs compared to 35.6 percent of people with LEP), Portuguese (22.1 percent compared to 15.3 percent), and Arabic (3.0 percent compared to 2.2 percent). Six languages have a lower share of ELLs than people with LEP: Chinese languages (4.4 percent compared to 20.1 percent), Haitian (4.5 percent compared to 6.7 percent), Vietnamese (1.7 percent compared to 4.6 percent), Russian (1.2 percent compared to 2.9 percent), French (0.7 percent compared to 1.5 percent), and Korean (0.6 percent compared to 1.2 percent).

This suggests those who speak Chinese, Haitian, French, Vietnamese, and Russian are more often older adults or adults without children who have a greater need for language services, whereas Portuguese, Arabic, and Spanish are more likely to be children and their families who require services. This information can help the MPO tailor outreach more effectively based on the communities and languages that are spoken.

Because of the nature of its activities, the MPO has variable and unpredictable contact with people with LEP. MPO staff undertake some engagement activities on a regular basis, such as biweekly MPO board meetings, monthly meetings of the MPO Advisory Council, the development of the annual Transportation Improvement Program and the Unified Planning Work Program, and the development of the Long-Range Transportation Plan, which is done every four years. Targeted engagement with LEP populations is part of these activities, but the frequency varies annually. Each year the MPO also funds studies, most of which contain an engagement element. The level of LEP engagement varies, depending on the study topic, study area, and resources available.

The MPO provides the same level of access to MPO online events as in-person events, providing interpreters and translations as requested and as described in Chapter 3. In addition, the MPO uses the translator service Localize to translate content on its website, which is an important contact point with the MPO for all members of the public. However, to date the MPO has had limited engagement with people with LEP via online engagement. Part of the reason may be a lack of awareness of the MPO and the challenge of engaging the LEP population in general. As described in Chapter 3, MPO staff are committed to building the relationships needed to engage people with LEP, and we hope that will reflect in stronger engagement at online meetings.

The MPO plans and funds transportation projects and carries out studies within the Boston region. However, it is not an implementing agency; therefore, project construction is the responsibility of municipalities, state transportation agencies, and/or regional transit authorities (RTA), each with its own policy for providing language assistance. However, MPO-funded transportation projects can significantly affect residents’ mobility and quality of life. Therefore, the MPO invests considerable effort to conduct inclusive public engagement to ensure all people have meaningful opportunities to influence MPO decisions and that projects that the MPO funds reflect their needs. Engagement is conducted largely through the MPO’s programs, which guide and inform investment decisions. Programs fall into several categories:

The precise nature and extent of the public engagement varies year to year but includes in-person and online meetings organized by MPO staff, as well as MPO staff attendance at existing public events and at partner organizations’ events. MPO staff view relationship building with LEP communities and organizations that serve them as an ongoing activity, whether or not it is for specific programs or activities. This allows staff to build trust over time, understand community needs, increase transparency, and ensure that people with LEP have opportunities to be involved early and often.

Because of the large number of Safe Harbor languages spoken in the Boston region, and the undue cost of providing this number of translations coupled with the limited demand, the MPO does not translate all vital documents into each language. Instead, the MPO budgets sufficient funds to translate vital documents into the five languages most widely spoken by people with LEP, which comprises more than 80 percent of people with LEP:

To reduce the cost burden on the MPO, as well as to tailor translations to community needs, engagement materials are translated only into the languages most commonly spoken in that community which may or may not be among the top five listed above, depending on the needs of the community. In addition, only executive summaries are translated for the longer vital documents due to their length. All of these documents are also made available in HTML on the MPO website, which can be translated using the MPO’s web translator, Localize. If a person requests a translation for a language other than these five, staff make every effort to accommodate it based on the resources available. If resources are limited, staff work with the requester to offer alternatives that meet their needs. Strategies for doing so depend on the size of the document being translated. Many smaller documents can be translated by professional translators. If resources do not allow this, staff will use machine translator services, such as Localize and Google Translate to provide the translation.

Resources are also allotted to provide interpreter services upon request at MPO-hosted meetings (such as board meetings). As with translations, staff bring interpreters to engagement meetings and events where it is expected people with LEP will be in attendance. Each year, staff budget for an estimated number of events where interpreters will be needed. Events are based on upcoming MPO studies and the expected public engagement that will be needed; meetings with community groups that serve people with LEP that staff are seeking to build relationships with; and attending events where people with LEP are likely to attend (such as farmers markets).

Chapter 3—Providing Language Assistance

The Boston Region Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) provides interpreter services upon request at all MPO-hosted events and meetings. The MPO contracts with an interpretation company that can provide interpreters for the most commonly spoken non-English languages:

Many other languages are available as well, including most of the MPO’s Safe Harbor languages. If a language is not available, staff make every effort to seek out other interpreter services that can provide the language requested.

Staff determine interpreter needs in several ways:

All notices for in-person events or meetings hosted by the MPO state how to request an interpreter by contacting the MPO’s Title VI Coordinator. MPO staff request that interpreter services are requested at least five calendar days in advance of the event; however, staff will do their best to accommodate requests made with less notice. It is also the MPO’s policy to bring interpreters to public meetings or other engagements at which non-English speakers are expected, regardless of whether they are requested or not.

While staff continue to use conventional online avenues such as the MPO website, MPO emails, and online surveys, the need to conduct public engagement virtually during the COVID-19 pandemic has led to more opportunities to engage with the MPO online. All MPO meetings and MPO-hosted public events are held via Zoom, which includes several interpreter lines in addition to the main English one. Staff make every effort to provide services equivalent to those offered at in-person meetings and tailor online engagement to the needs of the community and individual attendees, using the same four avenues described above. As with in-person engagement, attendees are asked to request an interpreter at least five business days ahead of time.

The MPO prioritizes providing written translations of vital documents, as required by federal regulations. Vital documents are those that contain information that is critical for obtaining MPO services or those required by law. The MPO has determined that documents and materials are considered vital if they enable the public to understand and participate in the regional transportation planning process. They include the following:

There are also vital MPO documents for which just the executive summary is translated into the MPO’s top five Safe Harbor languages due to their length. They include the following:

Most vital documents are translated into the region’s most commonly spoken non-English languages:

Vital documents are not translated into all Safe Harbor languages for several reasons:

The following section describes the MPO’s approach to translating the different types of vital documents and any exceptions to the policies just described.

These documents are translated in full into the region’s most commonly spoken non-English languages. Translations into other languages may be requested.

Executive summaries for core MPO documents are translated rather than the full document due to the documents’ length and therefore the prohibitive cost of translating them. All core MPO documents are posted on the MPO website in HTML and are therefore able to be translated by the MPO’s website translator, Localize, into the MPO’s top Safe Harbor languages. In addition, the executive summaries are meant to be a more public-friendly document than the main document itself. They contain information most relevant to the public, focusing on the results of the planning process, are written in plain language with engaging visuals, and are used by MPO staff during public events.

If a person requests a translation in a language other than the MPO’s top written Safe Harbor languages, the MPO makes every effort to accommodate that request based on the resources available. If resources are limited, staff will work with the requester to identify alternatives that meet their needs.

All materials for MPO board and committee meetings—agendas, minutes, and relevant work products—are posted on the MPO’s calendar. They are posted in both PDF and HTML formats; HTML can be translated into the MPO’s top Safe Harbor languages. Staff make every effort to post all materials seven days prior to the meeting, and always 48 hours prior. Members of the public may request translations of any of these materials within five days of the meeting, and staff will make every effort to accommodate those requests.

The website is an important tool through which the public interacts with the MPO and learns about its activities. The MPO uses Localize to translate its website, a browser-based tool that uses high-quality neural machine translation to translate content. As a rule, the MPO is committed to using professional human translators, as they provide the highest quality translations; however, the amount of website content and frequency with which it is updated makes that cost prohibitive.

Localize translates website content into the MPO’s top Safe Harbor languages (identified above). This covers more than 80 percent of people with LEP in the Boston region. As with other documents, anyone may request a translation of any part of the website into any language, and staff will make every effort to accommodate the request based on the resources available. Vital documents, as well as many others, are posted on the website in PDF and HTML; again, HTML can be translated by Localize. In addition, people with LEP may also set their internet browser language to one of their choosing, which Google Analytics statistics show is a common way that people with LEP acquire translations for the MPO website.

This subsection describes the MPO’s approach to providing translations for public engagement materials. To ensure the MPO invests in translations that are relevant, staff provide translations that are targeted for the audience and/or community in which the activity or event is being conducted, regardless of which language they speak. As with the provision of interpreter services, staff use several methods for making this determination:

If translations are needed, staff provide translations of all materials that a person would need to participate fully in a meeting or event. This includes agendas, presentations, surveys, and any materials relevant to the meeting topic. In general, every material that is available to English speakers is made available to non-English speakers. The subsections that follow describe the translation strategies for specific types of engagement materials.

Most MPO surveys are conducted online; however, paper versions are made available when needed and in cases where it is easier to distribute in this way, such as at in-person meetings. In both cases, survey translations are made available as described below.

Survey distribution and translation strategies are tailored to each survey. Surveys of a regional nature—in topic and/or study area, such as those developed for the Long-Range Transportation Plan Needs Assessment—are translated into all of the MPO’s top five Safe Harbor languages; translations into other languages are provided upon request. These surveys are distributed via channels that can reach a broad audience. This may include, but is not limited to, social media and email. To ensure surveys are reaching hard-to-reach populations such as people with LEP, staff partner with trusted community groups across the region to help distribute the survey.

With surveys for a project or study that is for a small geographical area (such as a municipality) or that is for a topic that is aimed at a particular audience (such as human service transportation), staff target them to the relevant communities and/or populations. Like other engagement materials, the languages that surveys are translated into are determined based on the demographics of the study or project area, as described above. Staff select a subset of languages in which to translate surveys into, considering all languages, not just the top ones, that reflect the communities’ demographics. Staff work with trusted community groups, including those who serve people with LEP, to help distribute the survey (including translated versions) through a variety of means, such as social media, emails, and in-person and/or virtual events.

Email is the main method by which MPO staff provide the public with updates on MPO activities and opportunities for engagement. Any member of the public may sign up for any of several MPO email lists. All emails can be translated by clicking where indicated at the top of the email. Translations are performed by Google Translate and are available in dozens of languages, including all of the MPO’s Safe Harbor languages. Other types of public notices may be used as well if needed, such as flyers, which are translated into the languages that staff have identified as most likely to be spoken by those in attendance, as described above. Similarly, where social media is used to communicate about an event, translations will be provided (for example, the translation of social media posts into Spanish for an event in a heavily Spanish-speaking area).

MPO staff regularly produce other engagement materials that meaningfully allow people to engage with the MPO and provide input into MPO processes. These materials are wide-ranging—they include but are not limited to

As with other engagement materials, staff determine translation needs based on the event, study, or other activity that the material(s) is being produced for. Staff ensure that the translations for engagement materials reflect the needs of the people and communities involved. For example, at an event where there are expected to be Portuguese speakers, all materials are translated, and interpreters are provided. Staff also consult trusted partner community groups and use US Census data to identify if a particular dialect is likely to be spoken (such as Brazilian Portuguese).

A person may request a translation of any document—whether or not it is considered a vital document—into any language, and staff make every effort to accommodate the request based on the resources available. If resources are limited, staff work with the requester to identify alternatives that meet their needs.

The MPO conducts studies each year on transportation topics relevant to the region and to support the MPO’s broader program goals. Most contain a significant engagement element and follow the interpretation and translation policies described above with reference to public engagement.

In addition, staff develop summary products at the completion of each study that summarize the major findings and are tailored to the study’s audience. This complements the technical report, allowing the study results to reach a broader audience. Using the approach outlined in the public engagement materials section, this document will be translated into the languages staff identified during the engagement portion of the study. Regardless, anyone may request it to be translated into any language and staff will make every effort to fulfill the request.

The MPO uses several different types of translation methods. Most documents are translated by professional human translators, as they provide the highest quality translations. All vital documents are translated in this way, except the MPO’s website, which is translated with neural machine translation through Localize. Neural machine translation provides a higher quality translation than statistical machine translation, which the MPO had used in the past before purchasing Localize in 2022. MPO emails, which are translated with Google translate, continue to be translated with statistical machine translation.

All MPO public documents—whether or not they are considered vital documents—contain a notice that they may be translated into any language upon request. The MPO translates documents on a first-come, first-served basis. As resources allow, staff will make every effort to provide translations of the full text and maintain the layout of the English version. If resources are limited, staff will work with the requester to identify alternatives that serve their needs.

Strategies to increase engagement with people with LEP are focused on more effectively targeting the MPO’s engagement with communities with higher rates of people with LEP to better understand and address language needs throughout the region. Effective recent engagement with people with LEP has included increased in-person events and activities, tactile and visual activities, and the provision of targeted translated materials and interpretation. Methods of engagement include direct in-person engagement by attending meetings held by organizations that include or serve people with LEP and tabling at community events in communities with LEP populations, developing materials tailored to attendees, and providing interpretation services, informed by staff’s analysis of where particular languages are spoken.

In addition, staff are developing long-term, non-project-based relationships with community-based organizations that include and/or serve people with LEP, and exploring partnerships with these organizations that include providing compensation or incentives to encourage their engagement. This ongoing process of relationship building helps build trust between the MPO and the communities it serves and allows staff to solicit input more effectively from hard-to-reach populations such as people with LEP at important points during project and planning work.

Chapter 4—Monitoring and Updating the Language Assistance Plan (LAP)

Although the MPO has been able to provide language translation services with existing resources thus far, the region continues to attract diverse ethnic and cultural populations. Therefore, the MPO will continue to monitor the need for translation and interpretation services based on the Four-factor Analysis, the number of requests received, and changing demographics of the region. As new language data become available and approaches to assisting people with LEP evolve, this LAP will be revised, at least every three years. In the interim, staff will explore new sources of data that provide more nuanced understanding of the language needs of residents in the region and new technologies that expand the reach of MPO activities to more people. To ensure more people with LEP are aware of the MPO and the services and programs it provides, staff will continue to build relationships with community organizations that serve people with LEP.

1 An ELL student is defined by the DESE as “a student whose first language is a language other than English who is unable to perform ordinary classroom work in English.” See http://profiles.doe.mass.edu/help/data.aspx?section=students#selectedpop.

2 Because only ACS data from non-overlapping years should be compared, this analysis compares the most recent ACS data with the most recent release with non-overlapping years.

3 An ELL student is defined by the Massachusetts Department of Education as “a student whose first language is a language other than English who is unable to perform ordinary classroom work in English.” See http://profiles.doe.mass.edu/help/data.aspx?section=students#selectedpop.

4 A few public-school districts include towns outside of the Boston region: King Phillips School District (which includes Plainville); Northborough-Southborough School District (which includes Northborough); Masconomet School District (which includes Boxborough); and the Nashoba School District (which includes Lancaster and Stow).