by Róisín Foley, MPO Staff

Conversations about improving transit access for underserved communities often revol ve around creating new service or implementing more frequent service on existing lines. However, recent work funded by the Boston Region Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) approaches the issue from a different angle. Casey-Marie Claude, Bicycle and Pedestrian Coordinator at the MPO, recently completed a study focusing on how the physical environment can form a barrier that discourages area residents from using the MBTA’s Fairmount commuter rail line. The study analyzed bicycle and pedestrian accommodations at five Fairmount Line stations, and offers concrete streetscape improvements that the City of Boston can implement to enhance the character of the neighborhoods near each station; create easy, safe, and pleasant access for bicyclists and pedestrians; and reduce nearby traffic congestion. This study follows on the heels of earlier staff work that explored safe access to MBTA stations.

ve around creating new service or implementing more frequent service on existing lines. However, recent work funded by the Boston Region Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) approaches the issue from a different angle. Casey-Marie Claude, Bicycle and Pedestrian Coordinator at the MPO, recently completed a study focusing on how the physical environment can form a barrier that discourages area residents from using the MBTA’s Fairmount commuter rail line. The study analyzed bicycle and pedestrian accommodations at five Fairmount Line stations, and offers concrete streetscape improvements that the City of Boston can implement to enhance the character of the neighborhoods near each station; create easy, safe, and pleasant access for bicyclists and pedestrians; and reduce nearby traffic congestion. This study follows on the heels of earlier staff work that explored safe access to MBTA stations.

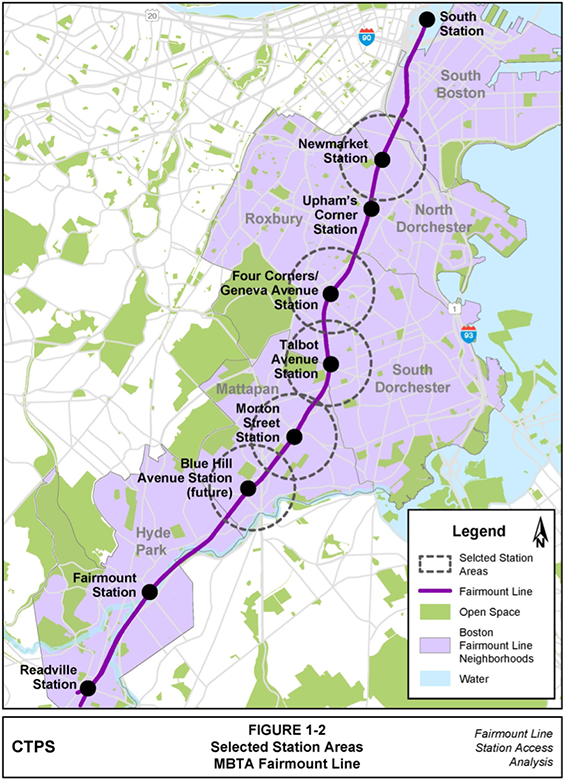

The Fairmount Line corridor stretches roughly nine miles from Readville in Hyde Park, through Mattapan, Dorchester, and Roxbury, to South Station. Boston’s recent citywide plan, Imagine Boston 2030, notes that the neighborhoods in the Fairmount Line corridor are “home to the city’s largest population of communities of color, sizable and growing immigrant communities, and Boston’s fastest growing population of school-aged children,” (page 262). “It is really an underused line,” says Claude. Boston Planning & Development Agency (BPDA) statistics show that in 2014, residents in the Fairmount Line corridor chose to drive to work at higher rates than those in the city as a whole (59 percent, as opposed to 45 percent for the whole city).

Part of this behavior may be the legacy of an historical lack of service. Passenger service on today’s Fairmount Line was abandoned in 1944. In 1979, the MBTA temporarily restored service when trains were redirected through Dorchester due to construction along the Southwest Corridor. Upon completion of the Southwest Corridor project in 1987, the MBTA planned to reassign most passenger service to the Orange Line. However, in response to public sentiment, the MBTA continued limited service between Readville and South Station, with intermediate stations at Fairmount, Morton Street, and Uphams Corner.

Beginning in the 1990s, community activists advanced a plan for the Indigo Line, a service similar to rapid transit, with more stops than commuter rail, increased service frequency, and a pre-pay fare system. However, the state agreed only to build new stations. Service from Talbot Avenue Station began in 2012. Service from Newmarket and Four Corners/Geneva Avenue began in 2013. Blue Hill Avenue Station is planned to open in 2019. In 2013, the MBTA changed all stations except Readville to Zone 1A, which reduced the cost of a ride to match the rapid transit service fare. And in 2014, hourly weekend service began.

Despite these improvements, ridership remains low. A lack of adequate bicycle and pedestrian accommodations can make stations inaccessible for residents who might otherwise choose to take the Fairmount Line. Claude adds, “It’s important to make sure that people feel safe and comfortable walking and biking. Increasing the number of riders who walk or bike to transit is good overall. Not only are those transportation modes cost-effective and healthy for individuals, but they also help the environment, as they reduce congestion and emissions.”

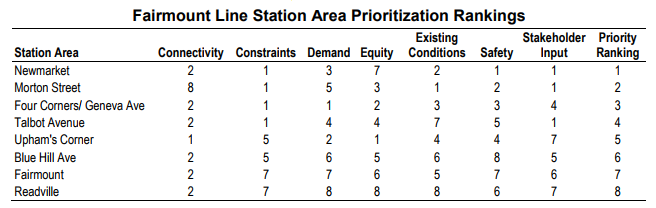

Claude used the ActiveTrans Priority Tool (APT) to determine which Fairmount Line stations were most in need of bicycle and pedestrian improvements. During the process of selecting stations for the study, she considered several factors: connectivity, constraints, demand, equity, existing conditions, safety, and stakeholder input. Some issues considered within these general categories were crash statistics, the prevalence of transit-dependent populations such as youth and the elderly, and potential future ridership demand. For example, the area around the future Blue Hill Avenue station anticipates 20 percent population growth by 2040. Blue Hill Avenue has the largest expected ridership of all stations in the corridor. Because not everyone will be able to park at the station, creating a safe walking and biking environment is a priority.

Claude walked and biked through all five station areas, assessing the condition of bicycle facilities, pedestrian signals, sidewalks, curb ramps, detectable warnings, and pavement markings. She amassed a massive set of data on current conditions and possible improvements that the city could use to make street-level progress on the short- and long-term goals for the Fairmount Line Corridor included in Imagine Boston 2030. Those goals include improving accessibility through “enhanced pedestrian and bicycle connections to the stations, improved entrances, and wayfinding, additional Hubway networks serving station stops, signs showing real-time bus and train-arrival information, and overall station safety,” (276).

inbound station platform. The Association of Pedestrian and

Bicycle Professionals recommends replacing this design with

inverted U or post and ring racks.

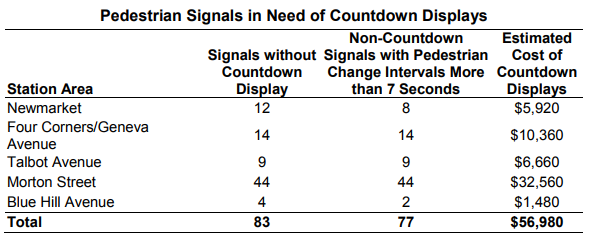

The study’s recommendations include bicycle facilities with a physical separation between the bicycle travel area and motor vehicle travel area, wherever feasible, and replacing bike racks with inverted U and post and ring designs. Recommended improvements for pedestrians include wider sidewalks, separate zones to house utilities, green space as a buffer from traffic, curb ramps with detectable warnings, visible crosswalk markings, and pedestrian signals with countdown displays that provide sufficient time for pedestrians to cross. The report includes cost estimates of each improvement (see figure 3 for an example), and tries to anticipate challenges that officials might encounter during implementation, as in situations where roads are owned by separate entities.

MPO board member and Senior Transportation Management Planner at the BPDA, Jim Fitzgerald thanked Claude and MPO staff for their work, and said that he believes the study would help the city to move forward with actual improvements.

The Fairmount/Indigo Community Development Corporation (CDC) Collaborative and its Fairmount Greenway Task Force are part of a growing network of residents, transit advocates, and non-profit groups that stand poised to follow up with the city on its goals for the Fairmount Corridor.

“It is often a concern that people don't feel safe walking and are too afraid to try biking,” says Michelle Moon, Fairmount Greenway Project Manager. The Fairmount Greenway is a proposed “multisite urban greenway with an on-street route along the Fairmount Corridor.”

Moon agrees that improving crosswalks in station areas would be beneficial, but stresses that the issue of encouraging walking and biking in Fairmount Corridor neighborhoods is not just about a lack of infrastructure. Moon cites a range of issues like reckless driving, neighborhood violence, fear of law enforcement, lack of access to bikes, and the need to change the perception of who exercises and bikes as contributors to lower rates of walking and biking in the Fairmount Corridor.

On the state side, Representative Evandro Carvalho recently proposed a bill that would create a two-year pilot shortening headways to 15 minutes during AM and PM peak periods, among other changes. At a hearing for Representative Carvalho’s bill, MBTA Advisory Board Executive Director (and MPO Board representative), Paul Regan testified that, "It's my own opinion that if they do this right, that particular corridor has the potential to match any other commuter line in terms of ridership. The potential is there for that to be a very, very popular and successful service."

Clearly there’s interest in making the Fairmount Line more like rapid transit, but with low ridership the MBTA seems reluctant to make significant investments. Claude characterizes the issue as a “chicken or the egg” kind of situation. If ridership were higher, the MBTA might see increased demand as justification for more frequent service. Conversely, if more frequent service were implemented, ridership might increase in response. The study proposes ways to improve access and hopefully increase ridership without significant changes to service. If successful, perhaps the MBTA will see the demand and be able to create rapid-transit-like service for the line in the long term.

Claude recognizes the impact of improving service on the line, “I think both things need to happen.” In the meanwhile, improving the public’s ability to safely and comfortably walk or bike to an existing or new station can be a short-term way to improve ridership and connect corridor residents to jobs and services.

More Information

The work discussed in this piece was funded through the MPO’s Unified Planning Work Program (UPWP). The UPWP programs studies and research projects that provide transportation planning and technical assistance to municipalities and agencies in the region. These studies focus on all modes of travel, with the goal of creating communities that are safe, accessible, walkable, bikeable, and resilient. MPO staff is now collecting ideas for the next UPWP. If you are interested in having a similar study conducted in your community, visit the UPWP Development Page to follow this year’s process.